My father was a hat manufacturer. Not hands-on. He was management, a director of his grandfather’s hat factory, entitled to sit in an office and shuffle papers, take business trips abroad, that sort of thing. But in fact he was a hands-on man.

In the early days of my research I visited the Hat Works Museum in Stockport, UK and was fascinated to find a comprehensive series of displays that answered many of my questions about the historical process of hat-making, about the Mad Hatter’s disease, and even a mock-up of a kitchen/parlour of the day showing the spartan conditions endured by most of the workers.

https://www.britainallover.com/2012/09/hat-works-museum-stockport/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hat_Works

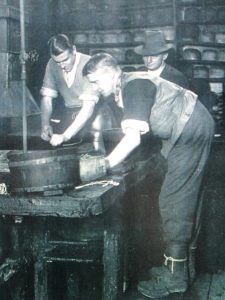

But I was unprepared for the blow-up photograph that confronted me as I rounded a corner.

My father on the left

There was my father, hands-on, on the factory floor with sleeves rolled up, working alongside the men. His preference.

He had beautiful hands with the long fingers of a pianist. One of the few memories I have of my father is of him playing the piano for me on a rare visit shortly before his suicide; we had a baby grand in our living room. He had wanted to be a concert pianist but, being the only son, he was obliged to work in the family business. Though I did not really know him, there are certain gestures that remain vivid, such as his hand thrown over the arm of the sofa, a cigarette dangling, smoke curling up from it. Perhaps my memories come from looking at family photos, or perhaps we record these images early in our lives, images imprinted on those round clear infant eyes that we watch with fascination from adulthood, wondering what the child is thinking.

When my father was detained without trial during the war, he was affectionately known in the camp as the “Mad Hatter” – a reference to his mistaken loyalty to Mosley’s untimely political cause, and to the hatter’s disease caused by mercury poisoning, until safer methods had been adopted at the turn of the century.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erethism

Erethism, also known as erethism mercurialis, mad hatter disease, or mad hatter syndrome, is a neurological disorder that affects the central nervous system, as well as a symptom complex derived from mercury poisoning. This was common among old England felt-hatmakers who had long-term exposure to vapors from the mercury they used to stabilize the wool in a process called felting, where hair was cut from the pelts of beavers and rabbits. The industrial workers were exposed to the mercury vapors, giving rise to the expression “mad as a hatter”. Some believe that the Mad Hatter in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is an example of someone suffering from erethism, but the origin of this account is unclear. The character was almost certainly based on Theophilus Carter, an eccentric furniture dealer who was well known to Carroll.

At an early stage in the writing I wanted to call this book Mad Hatter, but some members of my family responded negatively to the title. I did not want to upset them, and indeed in the early stages of writing I was hampered by a kind of guilt in revealing our shameful family secrets, even though there is a freedom and permission in fictionalizing a story. There is no solution to this kind of dilemma. A writer simply has to rely on the clarity and cleanness of their emotional motivation. In the end I stayed with that title because I discovered it to be emblematic of the contradiction that was our father. Due to his political stance and profession, he was initially dubbed “Mad Hatter” with an edge of derision but, because of who he was and how he handled his internment on the Isle of Man, developing a camaraderie with the many working class men interned with him, the nickname became a term of endearment and genuine affection.

I grew up middle class in class-bound Britain, seeing from my position both the oppression of the working class and the curse of privilege upon the upper class who generally live in a kind of comfortable confinement. This certainly was the case for my father as a boarding school boy bred on sports and music, growing up in an atmosphere of tradition and political naivete, largely in ignorance of the wider world. The family story goes that during his final year at school, in the sixth form, the boys were taken on a trip to London which included a tour of the east end. The poverty my father saw woke him up with a shock. He had not known that people lived in such conditions.

But his political awareness came too late. He soon became involved with Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists – at that time a popular political movement (see Cressida Connolly’s excellent novel After the Party). Mosley was influenced and supported by Mussolini, of whom Churchill was also an enthusiast. Mosley, another man of privilege, had the means to lobby for social and political change, and particularly for Appeasement – he was a veteran of WW1, had been wounded both physically, and by seeing the majority of his generation of young men slaughtered on the battle field.

Another interesting story in our family is my paternal grandfather’s miraculous survival of the WW1 sinking of the Lusitania. Grandpa had been away on hatting business in America and was sailing home on the Lusitania when it was torpedoed by the Germans on the south coast of Ireland. (See Dead Wake: the last crossing of the Lusitania by Erik Larson). He was found floating in the sea and his body was hauled into a lifeboat and laid out on the dock with the dead. But when a doctor came to inspect the bodies, he found Grandpa alive. According to family lore he was never the same. He would cry easily, especially after drinking; an emotionally traumatized man who was expected to carry on, which he did, and later expelled his son from the hat factory because he would not give up his involvement with Oswald Mosley’s political party.

Larson’s excellent book tells of the perhaps deliberate bungling of the Lusitania’s course, taking her south of Ireland, where German submarines were known to lurk, instead of to the north, a safer route. It is implied that Churchill may have engineered this, sacrificing the lives of predominantly American passengers in order to draw the USA into the war as Britain’s allies.

R to L my father, his sister Molly, Granny & Grandpa

I recently came across an article that cheered me, and which I believe would have pleased my father. The old hat factory in Offerton, near Stockport/Manchester, is to be converted into 144 affordable housing units. This is particularly interesting to me because I have a scene in my novel set in my grandfather’s office in this huge old brick building. It is good to know that the building, far from being demolished, is actually being converted into something appropriate to our times.